Conservation of energy

The nineteenth century law of conservation of energy is a law of physics. It states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system remains constant over time. The total energy is said to be conserved over time. For an isolated system, this law means that energy can change its location within the system, and that it can change form within the system, for instance chemical energy can become kinetic energy, but that energy can be neither created nor destroyed. In the nineteenth century, mass and energy were considered as being of quite different natures.

Since Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity showed that energy has an equivalent mass (see mass in special relativity), and mass has an equivalent energy, one speaks of a law of conservation of mass-energy as an updated version of the nineteenth century law. All particles, both ponderable (such as atoms) and imponderable (such as photons), respectively have both mass equivalents and energy equivalents. The difference between ponderable and imponderable particles is that ponderable particles cannot ever be accelerated to move at lightspeed, while imponderable particles always move at lightspeed (at least as to their phase velocity; they can exist as standing waves in a cavity with extremely reflective walls).

The total mass and the total energy of a system may both be respectively defined in special relativity, but for each, its conservation law holds. Particles, both ponderable and imponderable, are subject to interconversions of form, in both creation and annihilation. Nevertheless, in an isolated system, conservation of total energy and conservation of total mass each holds as a separate law.

A consequence of the law of conservation of energy is that no intended "perpetual motion machine" can perpetually deliver energy to its surroundings.

Contents |

History

Ancient philosophers as far back as Thales of Miletus c.~550 BCE had inklings of the conservation of which everything is made. However, there is no particular reason to identify this with what we know today as "mass-energy" (for example, Thales thought it was water). In 1638, Galileo published his analysis of several situations—including the celebrated "interrupted pendulum"—which can be described (in modern language) as conservatively converting potential energy to kinetic energy and back again. It was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz during 1676–1689 who first attempted a mathematical formulation of the kind of energy which is connected with motion (kinetic energy). Leibniz noticed that in many mechanical systems (of several masses, mi each with velocity vi ),

was conserved so long as the masses did not interact. He called this quantity the vis viva or living force of the system. The principle represents an accurate statement of the approximate conservation of kinetic energy in situations where there is no friction. Many physicists at that time held that the conservation of momentum, which holds even in systems with friction, as defined by the momentum:

was the conserved vis viva. It was later shown that, under the proper conditions, both quantities are conserved simultaneously such as in elastic collisions.

It was largely engineers such as John Smeaton, Peter Ewart, Karl Hotzmann, Gustave-Adolphe Hirn and Marc Seguin who objected that conservation of momentum alone was not adequate for practical calculation and who made use of Leibniz's principle. The principle was also championed by some chemists such as William Hyde Wollaston. Academics such as John Playfair were quick to point out that kinetic energy is clearly not conserved. This is obvious to a modern analysis based on the second law of thermodynamics but in the 18th and 19th centuries, the fate of the lost energy was still unknown. Gradually it came to be suspected that the heat inevitably generated by motion under friction, was another form of vis viva. In 1783, Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace reviewed the two competing theories of vis viva and caloric theory.[2] Count Rumford's 1798 observations of heat generation during the boring of cannons added more weight to the view that mechanical motion could be converted into heat, and (as importantly) that the conversion was quantitative and could be predicted (allowing for a universal conversion constant between kinetic energy and heat). Vis viva now started to be known as energy, after the term was first used in that sense by Thomas Young in 1807.

The recalibration of vis viva to

which can be understood as finding the exact value for the kinetic energy to work conversion constant, was largely the result of the work of Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis and Jean-Victor Poncelet over the period 1819–1839. The former called the quantity quantité de travail (quantity of work) and the latter, travail mécanique (mechanical work), and both championed its use in engineering calculation.

In a paper Über die Natur der Wärme, published in the Zeitschrift für Physik in 1837, Karl Friedrich Mohr gave one of the earliest general statements of the doctrine of the conservation of energy in the words: "besides the 54 known chemical elements there is in the physical world one agent only, and this is called Kraft [energy or work]. It may appear, according to circumstances, as motion, chemical affinity, cohesion, electricity, light and magnetism; and from any one of these forms it can be transformed into any of the others."

Mechanical equivalent of heat

A key stage in the development of the modern conservation principle was the demonstration of the mechanical equivalent of heat. The caloric theory maintained that heat could neither be created nor destroyed but conservation of energy entails the contrary principle that heat and mechanical work are interchangeable.

In 1798 Count Rumford (Benjamin Thompson) performs measurements of the frictional heat generated in boring cannons and develops the idea that heat is a form of kinetic energy; his measurements refute caloric theory, but are imprecise enough to leave room for doubt.

The mechanical equivalence principle was first stated in its modern form by the German surgeon Julius Robert von Mayer in 1842.[3] Mayer reached his conclusion on a voyage to the Dutch East Indies, where he found that his patients' blood was a deeper red because they were consuming less oxygen, and therefore less energy, to maintain their body temperature in the hotter climate. He had discovered that heat and mechanical work were both forms of energy, and later, after improving his knowledge of physics, he calculated a quantitative relationship between them (pub' 1845).

Meanwhile, in 1843 James Prescott Joule independently discovered the mechanical equivalent in a series of experiments. In the most famous, now called the "Joule apparatus", a descending weight attached to a string caused a paddle immersed in water to rotate. He showed that the gravitational potential energy lost by the weight in descending was equal to the thermal energy (heat) gained by the water by friction with the paddle.

Over the period 1840–1843, similar work was carried out by engineer Ludwig A. Colding though it was little known outside his native Denmark.

Both Joule's and Mayer's work suffered from resistance and neglect but it was Joule's that, perhaps unjustly, eventually drew the wider recognition.

- For the dispute between Joule and Mayer over priority, see Mechanical equivalent of heat: Priority

In 1844, William Robert Grove postulated a relationship between mechanics, heat, light, electricity and magnetism by treating them all as manifestations of a single "force" (energy in modern terms). In 1874 Grove published his theories in his book The Correlation of Physical Forces.[4] In 1847, drawing on the earlier work of Joule, Sadi Carnot and Émile Clapeyron, Hermann von Helmholtz arrived at conclusions similar to Grove's and published his theories in his book Über die Erhaltung der Kraft (On the Conservation of Force, 1847). The general modern acceptance of the principle stems from this publication.

In 1877, Peter Guthrie Tait claimed that the principle originated with Sir Isaac Newton, based on a creative reading of propositions 40 and 41 of the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. This is now regarded as an example of Whig history.[5]

First law of thermodynamics

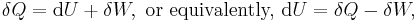

For a closed thermodynamic system, the first law of thermodynamics may be stated as:

where  is the amount of energy added to the system by a heating process,

is the amount of energy added to the system by a heating process,  is the amount of energy lost by the system due to work done by the system on its surroundings and

is the amount of energy lost by the system due to work done by the system on its surroundings and  is the change in the internal energy of the system.

is the change in the internal energy of the system.

The δ's before the heat and work terms are used to indicate that they describe an increment of energy which is to be interpreted somewhat differently than the  increment of internal energy (see Inexact differential). Work and heat are processes which add or subtract energy, while the internal energy

increment of internal energy (see Inexact differential). Work and heat are processes which add or subtract energy, while the internal energy  is a particular form of energy associated with the system. Thus the term "heat energy" for

is a particular form of energy associated with the system. Thus the term "heat energy" for  means "that amount of energy added as the result of heating" rather than referring to a particular form of energy. Likewise, the term "work energy" for

means "that amount of energy added as the result of heating" rather than referring to a particular form of energy. Likewise, the term "work energy" for  means "that amount of energy lost as the result of work". The most significant result of this distinction is the fact that one can clearly state the amount of internal energy possessed by a thermodynamic system, but one cannot tell how much energy has flowed into or out of the system as a result of its being heated or cooled, nor as the result of work being performed on or by the system. In simple terms, this means that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only converted from one form to another.

means "that amount of energy lost as the result of work". The most significant result of this distinction is the fact that one can clearly state the amount of internal energy possessed by a thermodynamic system, but one cannot tell how much energy has flowed into or out of the system as a result of its being heated or cooled, nor as the result of work being performed on or by the system. In simple terms, this means that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only converted from one form to another.

Entropy is a function of the state of a system which tells of the possibility of conversion of heat into work.

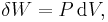

For a simple compressible system, the work performed by the system may be written

where  is the pressure and

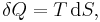

is the pressure and  is a small change in the volume of the system, each of which are system variables. The heat energy may be written

is a small change in the volume of the system, each of which are system variables. The heat energy may be written

where  is the temperature and

is the temperature and  is a small change in the entropy of the system. Temperature and entropy are variables of state of a system.

is a small change in the entropy of the system. Temperature and entropy are variables of state of a system.

Mechanics

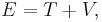

In mechanics, conservation of energy is usually stated as

where T is kinetic and V potential energy.

For this particular form to be valid, the following must be true:

- The system is scleronomous (neither kinetic nor potential energy are explicit functions of time)

- The potential energy doesn't depend on velocities.

- The kinetic energy is a quadratic form with regard to velocities.

- The total energy E depends on the motion of the frame of reference (and it turns out that it is minimum for the center of mass frame).

Noether's theorem

The conservation of energy is a common feature in many physical theories. From a mathematical point of view it is understood as a consequence of Noether's theorem, which states every continuous symmetry of a physical theory has an associated conserved quantity; if the theory's symmetry is time invariance then the conserved quantity is called "energy". The energy conservation law is a consequence of the shift symmetry of time; energy conservation is implied by the empirical fact that the laws of physics do not change with time itself. Philosophically this can be stated as "nothing depends on time per se". In other words, if the physical system is invariant under the continuous symmetry of time translation then its energy (which is canonical conjugate quantity to time) is conserved. Conversely, systems which are not invariant under shifts in time (for example, systems with time dependent potential energy) do not exhibit conservation of energy – unless we consider them to exchange energy with another, external system so that the theory of the enlarged system becomes time invariant again. Since any time-varying system can be embedded within a larger time-invariant system, conservation can always be recovered by a suitable re-definition of what energy is. Conservation of energy for finite systems is valid in such physical theories as special relativity and quantum theory (including QED) in the flat space-time.

Relativity

With the discovery of special relativity by Albert Einstein, energy was proposed to be one component of an energy-momentum 4-vector. Each of the four components (one of energy and three of momentum) of this vector is separately conserved across time, in any closed system, as seen from any given inertial reference frame. Also conserved is the vector length (Minkowski norm), which is the rest mass for single particles, and the invariant mass for systems of particles (where momenta and energy are separately summed before the length is calculated—see the article on invariant mass).

The relativistic energy of a single massive particle contains a term related to its rest mass in addition to its kinetic energy of motion. In the limit of zero kinetic energy (or equivalently in the rest frame) of a massive particle; or else in the center of momentum frame for objects or systems which retain kinetic energy, the total energy of particle or object (including internal kinetic energy in systems) is related to its rest mass or its invariant mass via the famous equation  .

.

Thus, the rule of conservation of energy over time in special relativity continues to hold, so long as the reference frame of the observer is unchanged. This applies to the total energy of systems, although different observers disagree as to the energy value. Also conserved, and invariant to all observers, is the invariant mass, which is the minimal system mass and energy that can be seen by any observer, and which is defined by the energy–momentum relation.

In general relativity conservation of energy-momentum is expressed with the aid of a stress-energy-momentum pseudotensor. The theory of general relativity leaves open the question of whether there is a conservation of energy for the entire universe.

Quantum theory

In quantum mechanics, energy of a quantum system is described by a self-adjoint (Hermite) operator called Hamiltonian, which acts on the Hilbert space (or a space of wave functions ) of the system. If the Hamiltonian is a time independent operator, emergence probability of the measurement result does not change in time over the evolution of the system. Thus the expectation value of energy is also time independent. The local energy conservation in quantum field theory is ensured by the quantum Noether's theorem for energy-momentum tensor operator. Note that due to the lack of the (universal) time operator in quantum theory, the uncertainty relations for time and energy are not fundamental in contrast to the position momentum uncertainty principle, and merely holds in specific cases (See Uncertainty principle). Energy at each fixed time can be precisely measured in principle without any problem caused by the time energy uncertainty relations. Thus the conservation of energy in time is a well defined concept even in quantum mechanics.

See also

- Conservation law

- Conservation of mass

- Energy quality

- Energy transformation

- Groundwater energy balance

- Laws of thermodynamics

- Lagrangian

- Principles of energetics

Notes

- ^ Walter Lewin (October 4, 1999) (in English) (ogg). Work, Kinetic Energy, and Universal Gravitation. MIT Course 8.01: Classical Mechanics, Lecture 11. (videotape). Cambridge, MA USA: MIT OCW. Event occurs at 45:35-49:11. http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/physics/8-01-physics-i-classical-mechanics-fall-1999/video-lectures/lecture-11/. Retrieved December 23, 2010. ""150 Joules is enough to kill you.""

- ^ Lavoisier, A.L. & Laplace, P.S. (1780) "Memoir on Heat", Académie Royale des Sciences pp4-355

- ^ von Mayer, J.R. (1842) "Remarks on the forces of inorganic nature" in Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 43, 233

- ^ Grove, W. R. (1874). The Correlation of Physical Forces (6th ed.). London: Longmans, Green.

- ^ Hadden, Richard W. (1994). On the shoulders of merchants: exchange and the mathematical conception of nature in early modern Europe. SUNY Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-791-42011-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=7IxtC4Jw1YoC., Chapter 1, p. 13

References

Modern accounts

- Goldstein, Martin, and Inge F., 1993. The Refrigerator and the Universe. Harvard Univ. Press. A gentle introduction.

- Kroemer, Herbert; Kittel, Charles (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- Nolan, Peter J. (1996). Fundamentals of College Physics, 2nd ed.. William C. Brown Publishers.

- Oxtoby & Nachtrieb (1996). Principles of Modern Chemistry, 3rd ed.. Saunders College Publishing.

- Papineau, D. (2002). Thinking about Consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

- Stenger, Victor J. (2000). Timeless Reality. Prometheus Books. Especially chpt. 12. Nontechnical.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0809-4.

- Lanczos, Cornelius (1970). The Variational Principles of Mechanics. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-1743-6.

History of ideas

- Brown, T.M. (1965). "Resource letter EEC-1 on the evolution of energy concepts from Galileo to Helmholtz". American Journal of Physics 33 (10): 759–765. Bibcode 1965AmJPh..33..759B. doi:10.1119/1.1970980.

- Cardwell, D.S.L. (1971). From Watt to Clausius: The Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-54150-1.

- Guillen, M. (1999). Five Equations That Changed the World. New York: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11064-6.

- Hiebert, E.N. (1981). Historical Roots of the Principle of Conservation of Energy. Madison, Wis.: Ayer Co Pub. ISBN 0-405-13880-6.

- Kuhn, T.S. (1957) “Energy conservation as an example of simultaneous discovery”, in M. Clagett (ed.) Critical Problems in the History of Science pp.321–56

- Sarton, G.; Joule, J. P.; Carnot, Sadi (1929). "The discovery of the law of conservation of energy". Isis 13: 18–49. doi:10.1086/346430.

- Smith, C. (1998). The Science of Energy: Cultural History of Energy Physics in Victorian Britain. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-485-11431-3.

- Mach, E. (1872). History and Root of the Principles of the Conservation of Energy. Open Court Pub. Co., IL.

- Poincaré, H. (1905). Science and Hypothesis. Walter Scott Publishing Co. Ltd; Dover reprint, 1952. ISBN 0-486-60221-4., Chapter 8, "Energy and Thermo-dynamics"

External links

- MISN-0-158 The First Law of Thermodynamics (PDF file) by Jerzy Borysowicz for Project PHYSNET.